RIVER HEALTH INDICATOR

HABITAT

Underwater and shoreline habitats play a critical role in the Potomac River’s ecosystem. Subaquatic grasses provide food and shelter to many species, add oxygen to the water, absorb nutrient pollution, and reduce streambank erosion. Riverside forests reduce water pollution by absorbing rainwater, stabilizing streambanks, and capturing excess nutrients.

The Potomac’s ecosystem is showing signs of resilience in times of extreme change. In 2018, record-setting rainfall contributed significant sediment pollution and likely caused degraded water clarity in the tidal portion of the river, yet encouragingly, underwater grasses and oxygen levels have remained steady over the last five years. A long-term decline in pollution has improved water quality in the non-tidal, upstream waters of the Potomac, but increasing levels of polluted urban runoff threaten this important progress.

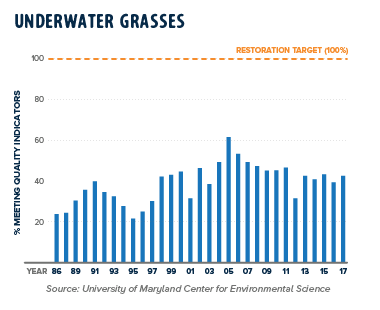

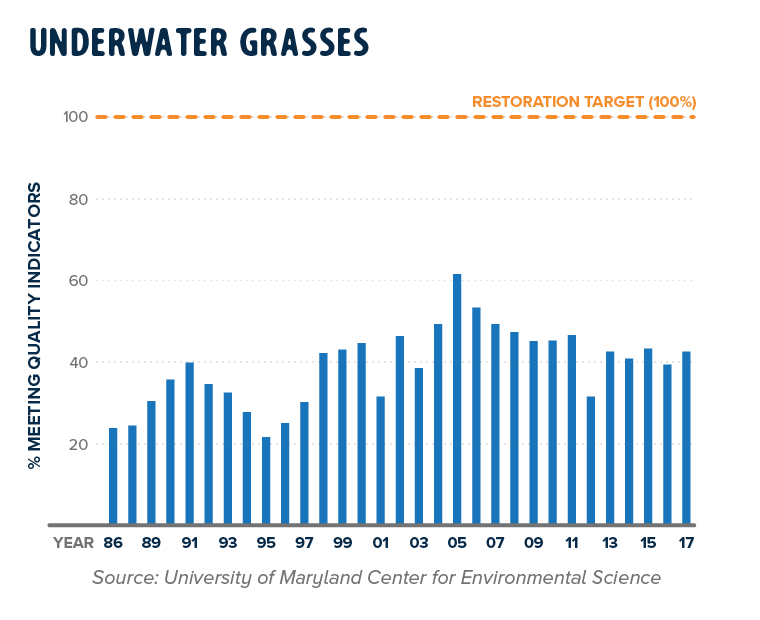

Underwater Grasses

Previous Grade: C-

Underwater grasses provide habitat for fish, waterfowl, and other wildlife. These grasses also add oxygen to the water, filter nutrients and pollution, and reduce shoreline erosion. Tidal grasses are great indicators of river health because they are sensitive to pollution but can quickly recover with water quality improvements. Significant challenges, such as highly turbid water and severe weather conditions, prevented a complete mapping of underwater grasses in 2018. As a result, portions of the Potomac River were not fully mapped. Tidal grass abundance is variable. A slight increase in total underwater grasses in the Potomac was observed in 2017, but the short-term trend since 2013 indicates coverage of grasses remains steady between 3,300 and 3,800 hectares (43 percent of the goal in 2017).

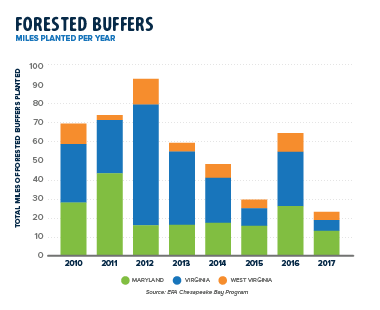

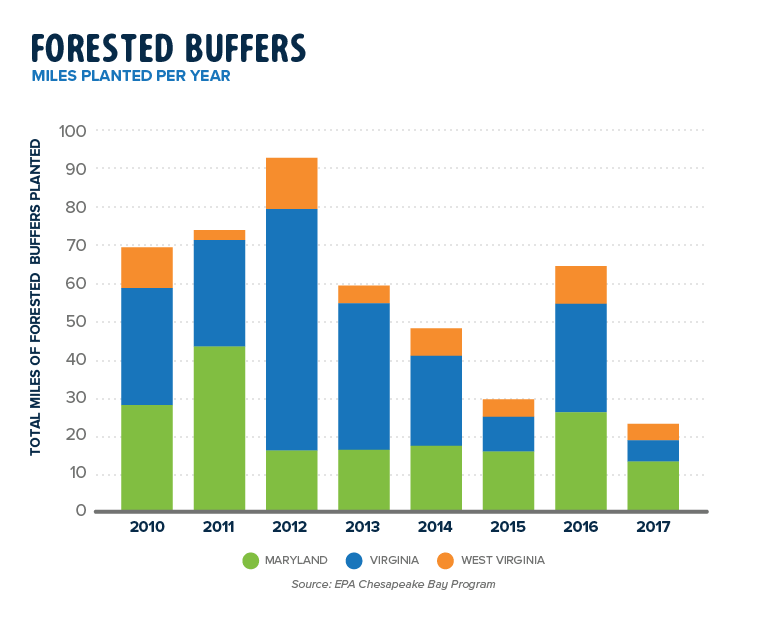

Forested Buffers

Previous Grade: F

Shoreline trees (also called forested buffers) offer crucial protection from the harmful effects of pollution in local streams and creeks. Forested buffers also provide important habitat for wildlife and reduce streambank erosion. Across the Chesapeake Bay watershed, forested buffer programs are falling short of restoration goals. The three states in the Potomac basin reported a combined 23 miles of riparian forest restoration projects in 2017, reaching only 11% of the goal.

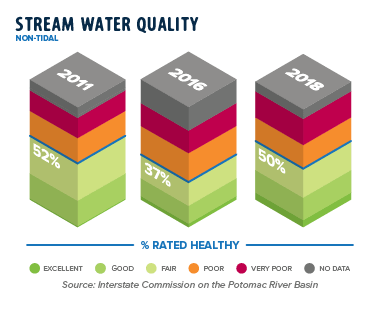

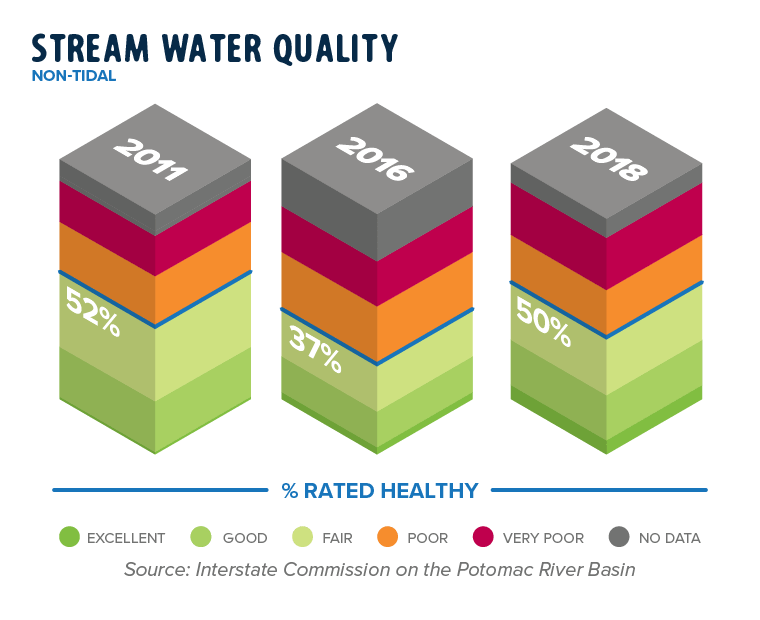

Stream (Non-Tidal) Water Quality

Previous Grade: C

Non-tidal water quality is often measured by observing macroinvertebrates: critters that live under rocks and plants in the bottom of riverbeds. Looking at the type and abundance of these critters in streams throughout the Potomac River region can provide clues regarding the health or impairment of the river. Based on assessments of macroinvertebrates using partial data, we estimate almost 50% of the small creeks and streams feeding the Potomac are healthy, meeting 71% of our goal. Note, we are investigating an updated index methodology for future reports because data challenges and changes to the methodology make it difficult to assess year-to-year changes on a consistent basis.

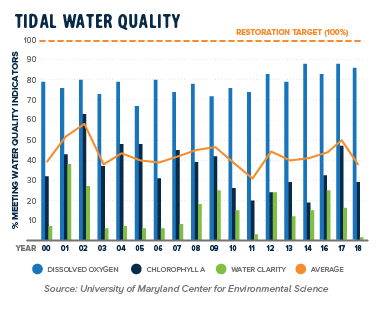

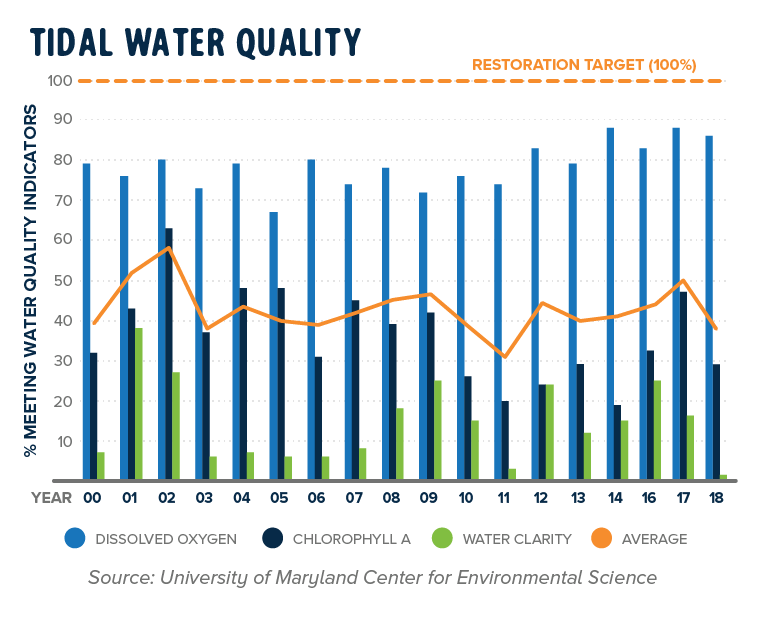

Tidal Water Quality

Previous Grade: C

Tidal water quality is measured by a combination of dissolved oxygen, water clarity, and chlorophyll a (a measure of algal biomass). Water clarity is a measure of sunlight penetrating through the water column, which indicates the amount of suspended sediment, plankton, or other organic matter in the water. Improved dissolved oxygen and water clarity in the Potomac can produce ideal conditions and habitat for fish and other aquatic life.

There have been long-term improvements in dissolved oxygen levels in the tidal Potomac region, but other water quality measures do not show consistent improvement over time. Water clarity in the Potomac experienced significant declines in 2017 and 2018, likely due to higher than average rainfall.

Chlorophyll a concentration is increasing in the short-term. Too much chlorophyll a indicates high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, which fuel harmful algal blooms. Algae blooms are harmful to aquatic life and can starve a river of critical nutrients. Some blooms can produce harmful toxins called cyanobacteria or microsystin which threaten animal and human health when ingested and are difficult to remove from drinking water supplies.

Resources and Methodology

Habitat indicators capture the quality of lands and waters in the Potomac, revealing the ability to support healthy populations of wildlife. To assess overall health, we use data from six areas, including tidal water quality, underwater grasses, forested buffers, and non-tidal water quality.

The Chesapeake Bay Program tracks and monitors forested buffers in miles. Forested buffer information is reported separately for different governmental programs, based on jurisdictions. Some statistics require voluntary reporting, such as the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP). Buffers have a credit duration of 10 years unless they are inspected and maintained.

There is no complementary program that exists for forested buffer plantings in urban and suburban areas. These areas rely on other types of programs, often with funding from state and local governments or grant programs, to plant and maintain trees. With no consistent framework, data is difficult to capture for these areas. Furthermore, the Chesapeake Bay Program tracks and monitors forested buffers in miles, not acres, making it difficult to consistently compare trends over time.

Data for the Habitat indicator are provided by the EPA Chesapeake Bay Program, the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, and the Center for Conservation and Biology at the College of William and Mary.

Habitat

Habitat Pollution

Pollution Fish

Fish Land

Land People

People Back to the River

Back to the River

Printed

Printed Press

Press