RIVER HEALTH INDICATOR

FISH

Fish serve as a helpful indicator species for the overall health of the Potomac River because they are sensitive to changes in their environment. An abundance and variety of fish species in a river is often a sign of good water quality.

After decades of decline, the Potomac is now healthy enough to support growing populations of shad, white perch, and other common game fish. Long-term trends signal that we’re beginning to reap the benefits of pollution-reduction, conservation, and re-stocking efforts.

Some fish species, including smallmouth bass, are showing signs of stress, possibly from environmental factors like heavy rains or overfishing. A very wet spring, like our region experienced in 2018, can significantly reduce juvenile numbers and impact future populations. There are worrying reports that striped bass populations have continued to fall in the last two years, a trend we will assess in the next report when data becomes available.

Pollution from excess nutrient and sediment runoff can alter and destroy aquatic habitat, decrease oxygen levels, and reduce the abundance of macroinvertebrates, an important food source for fish. Non-native invasive fish, disease, spring flooding, warming waters, endocrine disrupting chemicals, and PCBs also threaten the Potomac’s fisheries.

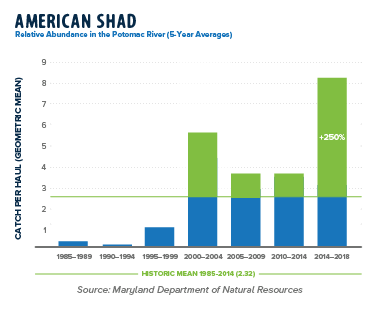

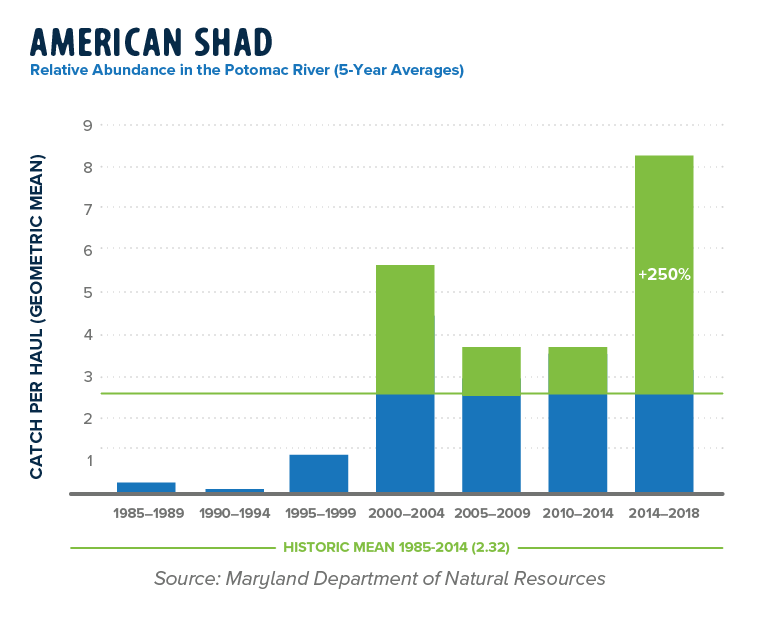

Shad

Previous Grade: A

American shad was once the largest commercial and recreational fishery along the Atlantic Coast, but a dangerous combination of dam construction, pollution, habitat degradation, and overfishing threatened the entire shad population.

A strict commercial harvest ban, initiated in the 1980s in both Maryland and Virginia began a long-term recovery effort. Where shad continue to struggle in the James River and other Chesapeake Bay tributaries, they are thriving in the Potomac. Since 2011, the species continuously exceeds restoration targets. The average abundance of shad between 2014 and 2018 exceeded the historic mean by 350 percent.

Anglers are allowed to catch and release, though commercial harvesting remains prohibited. In 2016, Mayor Muriel Bowser named the American shad the official fish of DC.

Disconcertingly, a new study raises concerns about the health of adult populations. A 2020 assessment by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, as reported by the Bay Journal, indicates that the rate of death among adult shad in the Potomac is unsustainable.

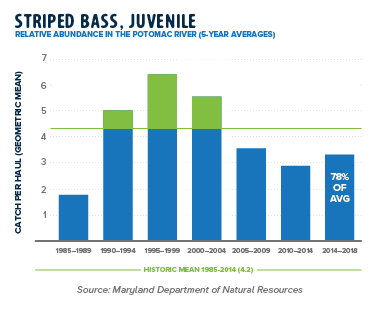

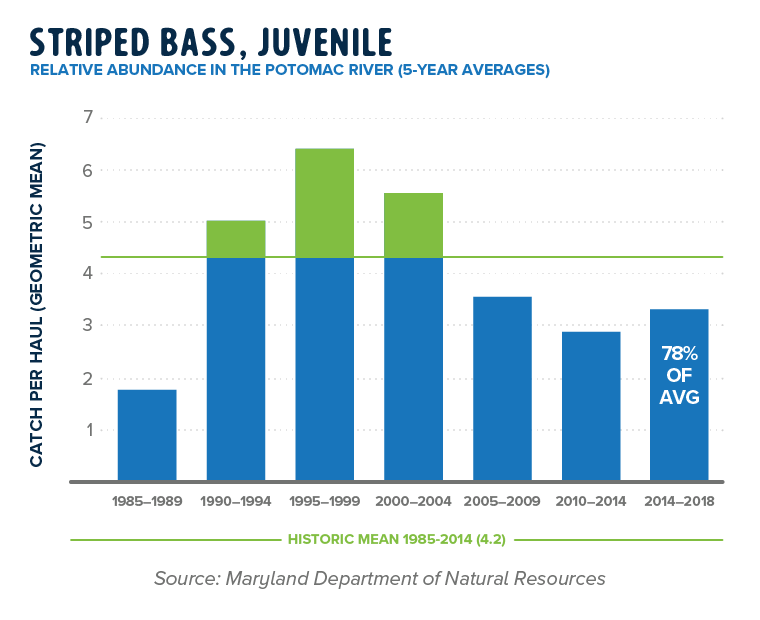

Striped Bass

Previous Grade: B-

Maryland’s state fish, the striped bass, experienced a difficult year throughout the region. Concerns about overfishing along the Atlantic coast led the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to close the 2019 striped bass fishing season in Virginia. Additional harvesting restrictions could soon be enacted by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. Because resource decisions are based on regional population trends, healthy populations can be seen locally while unhealthy populations could be found in other areas along the Atlantic coast. Average striped bass abundance in the Potomac River between 2014-2018 measures 78 percent of the historic mean.

Native fish populations are great for recreational fishing, but contaminants in the Potomac’s waters make many fish unsafe for human consumption. Washington, DC has advised against eating locally caught striped bass, one of the most popular catches for local anglers and Maryland’s state fish.

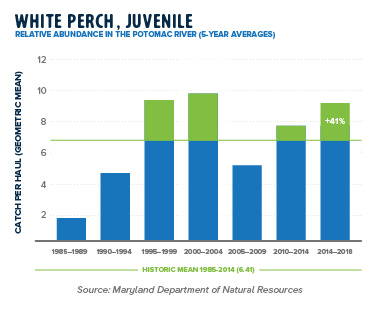

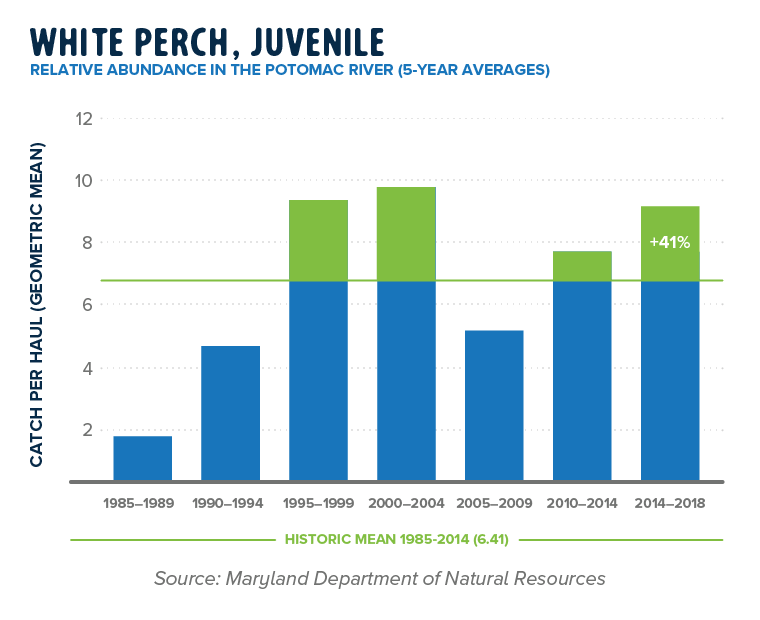

White Perch

Previous Grade: A

Another abundant and popular recreational fishing species, the white perch population in the Potomac River continues to thrive. In 2018, white perch abundance was up almost 200 percent over the historic mean, a nice rebound from 2016 and 2017 where abundance was below the historic mean. This is consistent with recent historical patterns of a very strong year following several years of weaker numbers. The five-year average survey results exceed the historic mean by 141 percent.

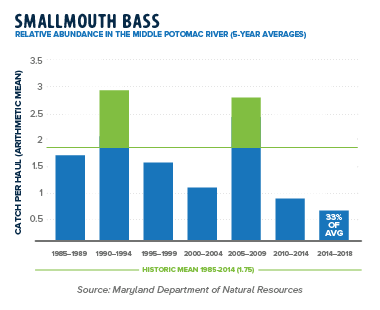

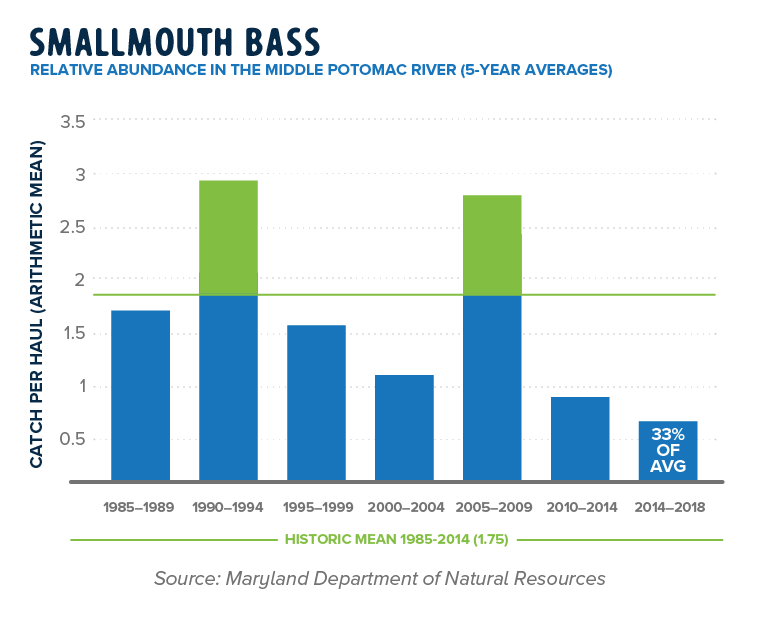

Smallmouth Bass

Previous Grade: C

Smallmouth bass struggled in 2017 and 2019; surveys weren’t conducted in 2018 due to heavy water flows. These fish species are considered good indicators of overall river health as they depend on good water quality, cool water temperatures, oxygen-rich waters, and healthy habitats such as underwater grasses. But, because of these qualities, they are particularly susceptible to high stream flows during in the spring when spawning typically takes place. Fisheries biologists and anglers in the area also suspect suppressed immune systems, invasive non-native fish, algae outbreaks, and increased fishing pressure are also negatively affecting this species. Since 2007, abundance of smallmouth bass has measured well below historic averages and only measured 33 percent of the historic mean from 2014-2018. Good water quality is required to support reproduction and strong recruitment of smallmouth bass.

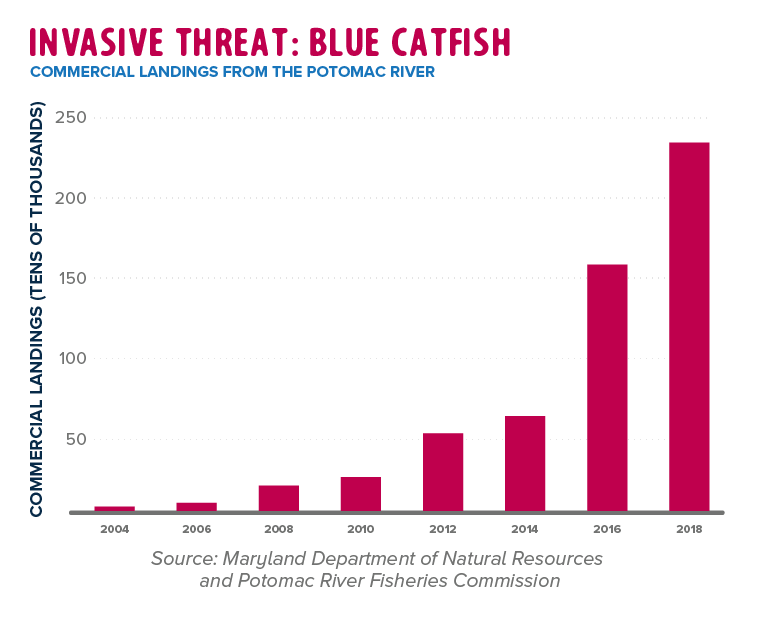

Blue Catfish (Invasive Threat)

Previous Grade: n/a

A non-native fish, blue catfish were first introduced to tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay in the 1960s and 1970s and have become popular with recreational fishermen. Their rapid expansion raised concerns about impacts on native species; this prompted the Chesapeake Bay Program to adopt a management strategy in 2012. The strategy recognizes the recreational value of the fish and possible ecosystem impacts if left unmanaged. Unfortunately, population data in the Potomac only goes back to 2013, making it difficult to determine the full extent of the catfish problem in the river and assess whether management strategies are working as intended. Commercial harvesting is considered a key management strategy for blue catfish in the Chesapeake Bay and tidal Potomac River. Limited catfish surveys in the upper (non-tidal) Potomac suggest the population is increasing.

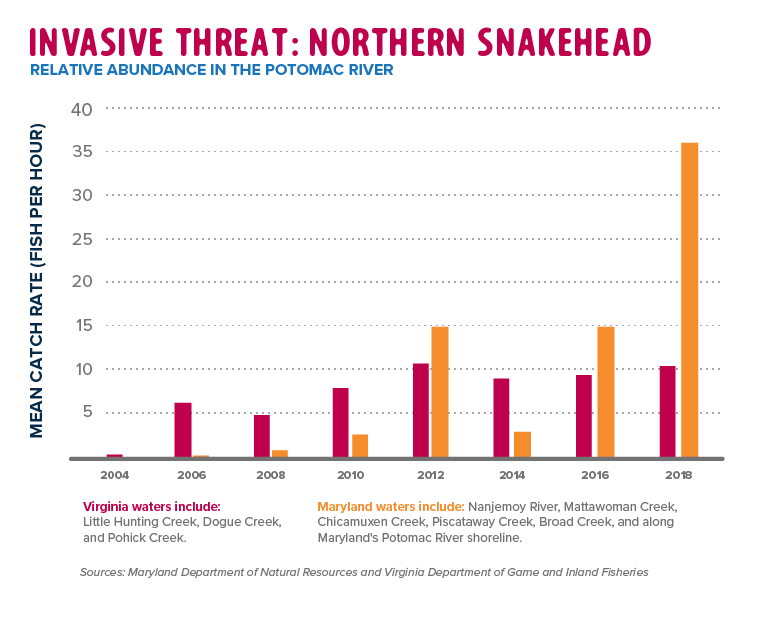

Snakehead

Previous Grade: n/a

Since 2002, the population of northern snakehead increased rapidly and expanded to multiple tributaries in Maryland and Virginia, even upstream of Great Falls which was considered a natural barrier. Scientists have reported variable population trends suggesting the invasive threat continues to exist and should continue to be closely monitored. Some studies indicate the population may be stabilizing despite the continual expansion of their territory, but one recent study suggests they are negatively impacting native fish species.

It is illegal to transport snakeheads across state lines without a federal permit. Officials from Maryland DNR advise anglers to harvest snakeheads if caught. In the event it has a tag, measure the length, make note of the exact location of capture, and call the number printed on the tag to assist with control and management strategies. Eradication measures have demonstrated mixed results. Tributaries with good public access and awareness by anglers have seen a decline in overall abundance. The opposite is true in tributaries with poor public access or where fishing for snakeheads is not as popular.

Resources and Methodology

The Potomac River is home to a diverse range of fish species. To assess overall fish health, we include historical data on common game fish including American shad, smallmouth bass, white perch, and striped bass.

Scientists use annual juvenile fish surveys to predict the health of adult population sizes in future years. Juvenile fish populations are naturally variable from year to year as weather and other environmental conditions can impact spawning and mortality rates. Studying long-term trends provide better insights into the overall health of a fish species.

Restoration goals do not currently exist for most species in this report and grades were determined by comparing the most recent 5-year average young-of-year survey mean to a 30-year historic average. Data are provided by the Chesapeake Bay Program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF), and the Potomac River Fisheries Commission (PRFC).

FISH

FISH Pollution

Pollution Habitat

Habitat Land

Land People

People Back to the River

Back to the River

Printed

Printed Press

Press